- Home

- John Powers

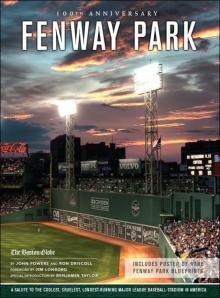

Fenway Park Page 3

Fenway Park Read online

Page 3

Joe Wood had been with the team since the late stages of 1908. He had come out of the West, the true “Wild West,” in his own words—born in the southwestern Colorado town of Ouray on October 25, 1889, and raised in Ness City, Kansas.

He was a sturdy 5-11 and 180 pounds, and Joe Wood had such a fastball that sometimes batters only saw the vapors; hence the nickname “Smoky Joe.”

“Can I throw harder than Joe Wood? Listen, my friend, there’s no man alive who can throw harder than Smoky Joe Wood.” So said Walter “Big Train” Johnson, who had a pretty good heater himself.

Smoky Joe, who was also known as the “Kansas Cyclone,” had 35 complete games in 38 starts, and in the opening game in New York, he beat the Highlanders with a seven-hitter while driving in two runs and fielding his position like a circus acrobat. By the end of May, word was out that the great Johnson had a major pitching rival in this young Mr. Wood. A tremendous crowd turned out at Griffith Stadium to see the two compete on June 26, and Smoky Joe sent them home with newfound respect after dispatching the Washington Senators with a three-hit shutout in the second game of a doubleheader. That made him 15-3 and gave him at least two victories over every opposing club in the eight-team league.

Wood entered August with a 21-4 record. He came out 28-4, and now thoughts were turning to an upcoming visit by the Senators, for Johnson was not relinquishing his title as Mound King easily. He was en route to a record-tying 16-game winning streak. It was becoming clear that a showdown was in order, and it happened on September 6 at Fenway.

It was the custom in those days to allow overflow fans to spill onto the outfield. Ropes were put up, and balls bounding into the crowd were ground-rule doubles. But such was the interest in this game that spectators were also permitted to line the foul lines, which no one had ever seen and would never see again. For the era, it was a massive crowd, estimated at 29,000.

Johnson was 28-10 and had just had a 16-game winning streak snapped. Wood was 29-4, with a 13-game winning streak. “One of the greatest pitching duels that has been fought should result,” said the Globe in a front-page story.

With such hype, there was scant chance of the game living up to its billing, except that it did. On a glorious late-summer afternoon, the Red Sox scored the game’s only run in the sixth when Tris Speaker doubled into the crowd in left and Duffy Lewis delivered him with a fly ball to right that ticked off Danny Moeller’s glove for another double.

Wood gave up six hits and walked three, but in the ninth, with a man on second base with one away, he got two strikeouts to end the game and give himself victory No. 30.

The Red Sox clinched the pennant with two weeks to spare and were honored with a parade from South Station to the Common. And guess who rode in the spot of honor?

The Red Sox expected to win the Series for one very simple reason. Sure, John McGraw’s Giants had the great Christy Mathewson, but in 1912, the premier pitcher in the land was Smoky Joe Wood. He beat the Giants, 4-3, in Game 1, finishing the game by striking out Otis Crandall to leave the tying run on second.

Wood pitched again in Game 4, with the Series tied at 1-1-1, Game 2 having ended at 6-6 when darkness prevailed. He mixed his pitches well and beat the Giants, 3-1, prompting Mathewson, in his ghostwritten newspaper column, to say, “His was the work of an artist.” Wood also drove in the third run in the ninth inning.

But given a chance to conclude the Series with Boston ahead, 3-2-1 in Game 7, Joe Wood could not tie the ribbon on the package. He was removed after one horrible inning in which he gave up six hits and was reached for a double steal.

It looked as if Wood’s storybook season would have a very inappropriate ending. The following day, Jake Stahl brought him out of the bullpen in the eighth inning of a 1-1 game. Wood threw two shutout innings before New York pushed across a run in the top of the 10th and would have scored another one if Joe hadn’t made a tremendous barehanded stop of a Chief Meyers line drive to the box. At any rate, he was the losing pitcher of record until his team came to bat. But the Red Sox, aided by some storied Giants misplays (the Fred Snodgrass muff of a routine fly ball and a Speaker pop foul that fell among three Giants), scored twice in the bottom of the inning. Joe Wood had his third Series win and the Red Sox had the 1912 world championship.

It is all in the books. In 1912, Wood had a league-leading 10 shutouts. He won 16 straight games. He threw 344 innings. He hit .290 and slugged .435. He won games with his glove. He won three games in the World Series.

Mayor John Fitzgerald (the celebrated “Honey Fitz”) orchestrated a massive civic celebration for the Red Sox. Joe Wood simply got up and said, “I did all I could, and I just want to thank you.”

“When I brought my kids to Fenway, they never complained about the inconveniences of the ancient ballpark. . . . I still take some weird comfort in the knowledge that the poles that occasionally obscured our view of the pitcher are the same green beams that blocked the vision of my dad and his dad when they would take the trolley from Cambridge to watch the Red Sox in the 1920s.”

—Dan Shaughnessy, Boston Globe sports columnist

Fans filled the third-base grandstand, as well as the temporary stands erected against the left-field wall, for the 1912 World Series against the New York Giants.

“I didn’t seem to be able to hold the ball,” he later told the New York Times, saying that the error “froze him to the marrow.” The ball “just dropped out of the glove and that’s all there was to it.” Snodgrass immediately made amends by snagging Harry Hooper’s shot to deep center. The real killer miscue was a miscall by New York pitcher Christy Mathewson on Speaker’s foul pop-up, which fell uncaught. Speaker then knocked in the tying run and Larry Gardner’s sacrifice fly scored Boston’s Steve Yerkes with the winner, setting off what the Globe’s Murnane called an “outburst of insane enthusiasm.”

There was another celebratory parade the next day, this one from Park Square to Faneuil Hall, where Mayor John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald proclaimed the Sox victory “an epoch in the history of this city.”

The euphoria continued throughout the winter, with a reprise assumed all around. “The more I think it over, the more convinced I am that we will be stronger next season than we were last,” McAleer said in February. So the 10-9 loss to Philadelphia in the home opener was shrugged off. “What’s One Lost Game to a Team That Can Win 105 in a Year?” asked the Globe headline.

But by April 20 the Sox found themselves in seventh place, and there was “shock over the Red Sox start.” Injuries didn’t help. Wood hurt his thumb while slipping as he was fielding a bunt and left fielder Duffy Lewis, shortstop Heinie Wagner, and the team’s player-manager Jake Stahl were all sidelined. “Having had their spring vacation, it is to be hoped that the Red Sox are now going to work with renewed vigor,” the Globe observed on May 11, when the club was in sixth.

Babe Ruth in 1915, age 20, when he won 18 games for the Red Sox and helped them win the first of three world championships in four years, before his infamous trade to the Yankees.

“MRS. JACK” WAS AN EARLY FANATIC

As the Globe’s Jack Thomas wrote in 1988: “There was only one Isabella Stewart Gardner, which is too bad, for nobody was better at shocking Boston society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and Boston today could use another like her. She is remembered not only for the Gardner Museum that she built with her husband’s money, but also for her impact on Boston’s cultural and social history from her arrival in 1860 as Jack’s 20-year-old bride until her burial in Mount Auburn Cemetery in July 1924.

“She was not even born in Boston, as her biographer pointed out. Jack met her in New York, married her two days before the Civil War began, brought her to Boston and moved into the Boylston Hotel, later the Touraine, until their house at 152 Beacon Street was built. She was aristocratic, eccentric, and scandalous. Her husband had money and patience and, being married to her, needed both. She demonstrated contempt for propriety by walking down Beacon Street with

pet lions, and posed in a low-cut dress with pearls around her hips for a John Singer Sargent portrait considered so risqué that when it was displayed at the St. Botolph Club in the winter of 1888, Jack ordered it taken down, and it was never again shown in his lifetime.”

Mrs. Jack, as she was known, once caused another huge commotion at Symphony Hall. In December 1912, two months after the Red Sox beat the New York Giants in the World Series, she appeared at a concert wearing “a white band around her head and on it the words, ‘Oh you Red Sox’ in red letters,” as a Boston gossip columnist put it. “It looked as if the woman had gone crazy . . . almost causing a panic among those in the audience who discovered the ornamentation, and even for a moment upsetting [the musicians] so that their startled eyes wandered from their music stands.”

Why the hubbub? “‘Oh you Red Sox’ was a song popular with the Royal Rooters, a group of Boston baseball fans known for rowdyism,” Patrick McMahon, a Museum of Fine Arts curatorial project manager, told the Globe in 2005. “Symphony-goers must have thought for a moment that one of those raucous drunks had slipped into the building.”

Mrs. Jack wasn’t just jumping on the bandwagon, insisted Gardner Museum archivist Kristin Parker. While perusing Gardner’s scrapbooks in 2005, Parker found numerous Red Sox news items, photos, and notations of scores dating to the Boston Americans’ triumph in the first World Series in 1903. In 1912, the 72-year-old Gardner purchased season tickets to the newly built Fenway Park, a stone’s throw from her palazzo. “One of the only things that kept [humorist] Robert Benchley from going ‘crazy with boredom’ in Boston in the summer of 1912, I’ve read, was meeting Gardner,” Parker said. “She took Benchley to Fenway, where she ‘loudly encouraged all the Boston players by name.’”

She was once called Boston’s most famous “insider outsider,” and some wondered about the death of her infant son, her only child, and whether the magnificent palazzo in the Fenway was a memorial to him. In one of the museum’s paintings, a Madonna and child by the Spanish artist Francisco de Zurbaran, she must have seen, as others have, that the child in the painting looked remarkably like one of the photographs of her little son. A Globe story about a museum renovation in 1928 said: “Everything was put back in its place, so the museum looks exactly as it did when Mrs. Gardner died. Nothing has been added, nothing removed. That is as she wished—and willed—it should be.”

More recently, in a nod to Mrs. Jack’s baseball allegiance, anyone wearing a Red Sox-branded item receives $2 off admission to the Gardner. If you’re named Isabella, you get in free—for life.

Portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner by John Singer Sargent, 1888.

IT WAS HIS CLIFF

He was a member of the Red Sox outfield that many consider to be the best in baseball history. He saw the first home run Babe Ruth hit and the last, No. 714. He is also one of the few players to ever pinch-hit for the legendary slugger.

They even named a cliff after him.

He was the venerable George “Duffy” Lewis, a Red Sox outfielder in the early glory days of World Series victories and later a traveling secretary for the Boston Braves. He was one-third of the famed Lewis-Speaker-Hooper outfield that sparked the Red Sox to World Series triumphs in 1912 and 1915.

After an outstanding career as a player that started with the Red Sox in 1910, Lewis was also a coach, manager, owner, and, finally, traveling secretary for the Boston and Milwaukee Braves, before retiring in 1961.

Born April 18, 1888, in San Francisco, George Edward Lewis was one of three children. His mother’s maiden name was Duffy and somehow that became his nickname. Along with his lifelong friend and fellow outfielder, Harry Hooper, Lewis attended St. Mary’s College in Oakland, California. In 1908, the pair played in the so-called “Outlaw League” in California and then jumped to the state’s City League.

Lewis came to the Red Sox from Oakland in 1910, joining Hooper, who had been brought up the year before. Lewis had been spotted and signed by John I. Taylor, owner of the Red Sox, for a $200 bonus. His first year’s salary was $3,000 and his biggest contract as a Red Sox outfielder was for $5,000.

When Lewis came up, the Red Sox had Tris Speaker in center, Harry Niles in right, and Harry Hooper in left. The Sox lost the first three games. Lewis was put in left and Hooper moved to right. Lewis’s hitting won the first game he played in for the Sox and he remained in left for the next 151 games. That established the Red Sox outfield for the next six seasons.

As the Red Sox left fielder, Lewis patrolled the most unusual parcel of real estate of any ballpark in America. Fenway’s left field then included a precarious grassy slope rising about 10 feet to the base of the wall. A player had to be part mountain goat to scale it, catch an outfield fly, and then stride downhill to throw the ball into the infield.

“The first time I saw it,” Lewis recalled in an April 21, 1978 Globe story by Joe Dinneen, “I said to myself, ‘Holy cow! What have we got here?’ It looked pretty awesome.”

Lewis would go out to the park early and have somebody hit the ball again and again out to the wall. He experimented with every angle of approach up the “cliff.” He mastered the slope so well that it was referred to as “Duffy’s Cliff.”

Bulldozers knocked the cliff down to just about level when Tom Yawkey remodeled Fenway Park in 1934.

The Red Sox enjoyed their most successful seasons during the stewardship of their mighty outfield trio. In 1912, they beat the New York Giants in seven games in the World Series, but Lewis’s real starring roles were to come in Boston’s 1915 and 1916 Series wins.

In 1915, the Red Sox faced the Philadelphia Phillies, led by the great pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander. But Boston clobbered the Phillies, winning four of five games, losing only the first to Alexander. Duffy led all the regulars with a .444 average.

“They taught me how to go up the hill, but they didn’t teach me how to go down.”

—A visiting left fielder in the days of “Duffy’s Cliff”

T.H. Murnane of the Globe wrote, “Duffy Lewis was the real hero of this Series, or any other. I have witnessed all of the contests for the game’s highest honors in the last 30 years and I want to say that the all-around work of the modest Californian never has been equaled in a big series.”

In 1916, the Red Sox had to defend their championship without Speaker, who was traded to Cleveland just before the season. After securing the pennant, they faced Brooklyn in the World Series, and again the Sox prevailed by a 4-1 margin as Lewis batted .353. Lewis played with the Red Sox through 1917, spent some time in the Navy during World War I, and then was with the Yankees for two seasons before winding up his playing career with one season in Washington.

Lewis was an established player when Babe Ruth came up to the Red Sox as a pitcher in 1914. Ruth had a terrible memory for names and always greeted everyone with, “Hi, kid.” For some reason, Duffy recalled, Ruth remembered him and always saluted him with, “Hi, Duff.”

The Babe, Lewis said, was a pretty fair hitter in his early days, but had a habit of striking out a lot. And that’s how Lewis came to pinch-hit for the Sultan of Swat.

“I was on the bench nursing a bad ankle,” Lewis recalled. “Bill Carrigan, our manager, asked me if I could hit. I said sure. So he sent me to pinch-hit for Ruth. I got a hit, too. I used to think it won the game, but someone told me a few years ago that it didn’t.”

In 1947, Lewis received a testimonial dinner at the Hotel Statler, with more than 1,000 friends and fans turning out. He was reunited for the evening with old outfield compatriots Speaker and Hooper.

Lewis threw out the first pitch to open the 1975 World Series at Fenway Park. Perhaps the only sad note in his long baseball career is that it did not end with a place in the Hall of Fame.

Speaker had been part of the Hall’s second group in 1937. Hooper was inducted in 1971 and spent the remaining years of his life plugging for Duffy to make it.

Frank Frisch, a member of the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee

, once told Lewis: “You, Speaker and Hooper all should have gone into the Hall of Fame at the same time. As the best outfield of your day, it would have been right.”

Lewis shrugged it off. “A lot of people have said I should have gone in with the others. But I have no regrets. I’m doing all right.”

Duffy Lewis died in Salem, New Hampshire, in 1979 at the age of 91. He was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame in 2002.

The 10-foot-high incline in left field that abutted the wall (visible behind players) was named for Duffy Lewis (opposite page), the Red Sox left fielder who mastered its vagaries.

LENDING AN EAR TO DE VALERA

Eamon de Valera, president of the Irish Republic, came to America in 1919 to plead the cause of independence for the fledgling Irish state, and his visit to Boston brought a massive crowd of 50,000 to Fenway Park.

The Globe’s A.J. Philpott wrote, “It was an inspiring assemblage—one in which the spirit of the Irish people rose above the spirit of faction, of group or party.” Of the Irish president, he wrote, “The very mystery which attaches to this man, who was comparatively unheard of until recently, somehow fulfilled the dreams of the race—that some great figure would arise at the crucial moment and lead Ireland to freedom. In the thoughtful, militant, clean-cut face and gaunt personality of de Valera there is somehow also personified that new spirit which has come to Irishmen in which the demand has superseded the appeal for justice to Ireland. In that vast audience, you sensed this new dignity that has sunk into their consciousness.”

Fridays with Bill

Fridays with Bill Fenway Park

Fenway Park